Polyvagal Mindfulness

Current Status

Not Enrolled

Price

Closed

Get Started

This course is currently closed

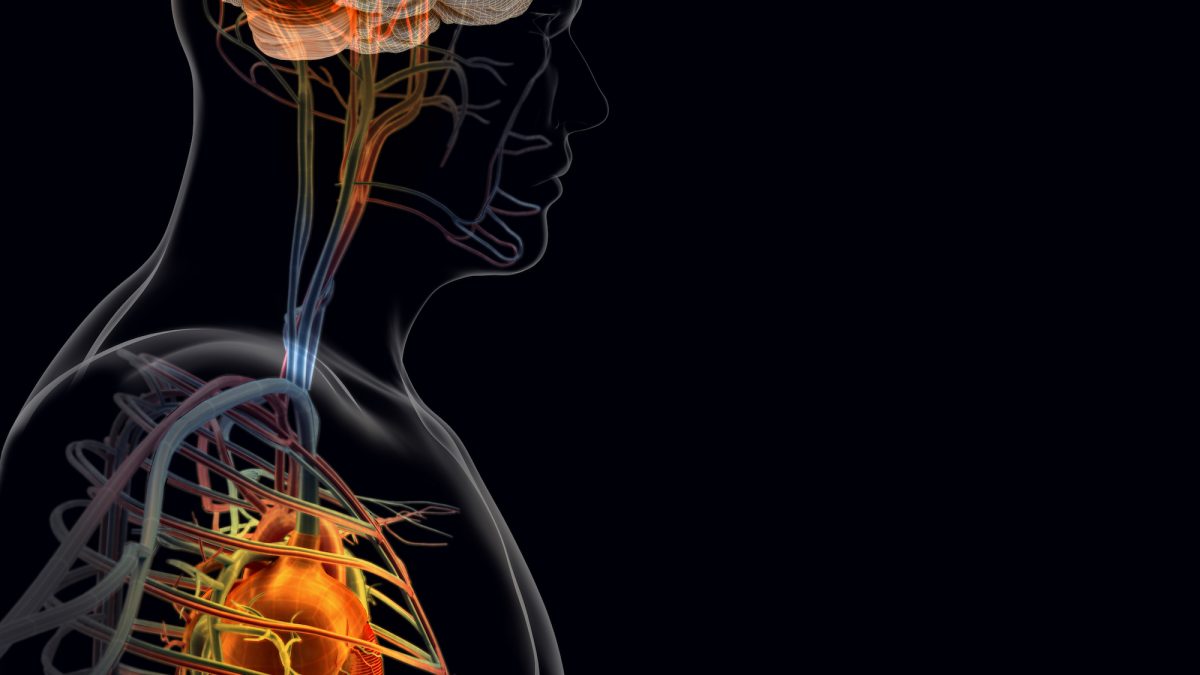

Welcome to the Polyvagal Mindfulness Course!

In this course, specifically created for health professionals and interested lay people, you will learn the foundations of the Polyvagal Theory, and a variety of Restorative Practices that you can engage personally, and/or utilize with patients/clients to support their well-being.